The trout water of Oregon’s Columbia Gorge spawned Phil Hilbruner’s love of fly-fishing. Phil grew up in Hood River, 45 miles east of Portland on the Columbia River, a short cast from the Deschutes and other rivers that piqued his boyhood curiosity. Now the 30-year old is launching into his third season as owner/operator of Catch A Drift, a drift-boat fly-fishing business on the world-renowned Kenai river in Alaska and it’s clear the proud business owner is as excited about fishing today as he was as a little boy.

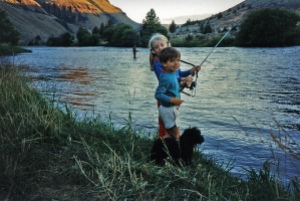

As a little kid, Phil was intrigued by his dad’s fly-tying hobby and his dad took notice. “He was pretty awesome about getting me started and teaching me. He saw that I really wanted to do it.” His dad supplied a vice and the necessary tools and extended him free reign of his materials. By the time he was 8 or 9 he was selling flies to The Gorge Fly Shop in Hood River. “I dunno what the owner was doing with those flies, if he was actually turning them around and selling them or if he was throwing them away or if he was using them himself or what.” Inarguably, he was stoking Phil on tying flies and fly-fishing.

Wonderment rippled through the young angler’s river days. “I remember, like, sailing in the Columbia and saw this huge chinook tail—it had just jumped and it was going back in the water. It was twice as big as me as a kid.” Although Phil played soccer, baseball, and ran track, organized sports never compared to the mystery of the river. “Fishing—it’s like a different world in the water.” Phil was increasingly drawn to the rivers but a jarring move to Maryland as an eighth-grader disrupted his intimacy with trout water.

He felt ripped out of his habitat; as stark a contrast as freshwater to saltwater. He had developed a fond appreciation for nature but eastern rivers didn’t harbor the magic of those he’d abandoned. He fished on, but his heart yearned for the west coast.

Alaska beckons

After high school, Phil’s priority was to move back west. College wasn’t immediately important. “I didn’t want to waste a bunch of money and get in all this debt.” He hoped to figure out what appealed to him at which point he’d acquire the necessary education.

After high school, Phil’s priority was to move back west. College wasn’t immediately important. “I didn’t want to waste a bunch of money and get in all this debt.” He hoped to figure out what appealed to him at which point he’d acquire the necessary education.

His sister worked in Denali National Park and she encouraged Phil to apply, as well. Employment included room and board for a nominal fee and Phil, almost broke, was sold. “When I got on the bus to go up to Denali in Anchorage I had twelve dollars in my pocket, and I spent six of those dollars on flip flops to shower in Wasilla.” The move didn’t immediately return Phil to desirable fishing water. The glacial waters of the north side of the Alaska Range support little aquatic life, and he was without wheels or a fishing rod anyway.

A few years later, directionless and desiring change, Phil experimented with life in Anchorage, a metropolitan access point near Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. One day, a coworker shared photos of large rainbow trout he’d caught on the Kenai River, and Phil begged to be taken the following weekend. “The first day I caught a rainbow three times bigger than the biggest one I’d ever caught, if not bigger. I mean, just 28-incher. That was it; I was hooked.”

For a couple years, Phil worked minimal-pay customer service jobs three or four days a week and tried to fish the other three or four—often hitching rides or borrowing cars to get down to the Kenai. Eventually, he returned to Denali where a significant wage increase allowed him to catch up a little bit financially. “At the end of that season I bought a piece of shit van, took it down to Cooper Landing, and got a brand new, nice fishing rod and a little pontoon one-man rowboat.” He camped out on the Kenai for six weeks, and as the Kenai revealed itself to him, he realized there was more potential on that river than he’d imagined. Back in Anchorage, however, he floundered. Finally, a non-profit job that paid eight dollars an hour to, among other things, power-wash human feces off roads became his breaking point. “One day I was just on a break at work and I realized: this is fucking miserable. I need to start pursuing what I want to do.” It was a blessing in disguise.

Take me to the river

Phil needed a job to position him in Cooper Landing and allow him to truly learn the Kenai. Any job. Search engines directed him to Kenai Cache and the owner enticed Phil with an intern guide program, a somewhat misleading description. Essentially, he worked at the tackle shop and if the guides used the boats for fun-fishing he had a guaranteed seat.

But Phil came prepared with a keg of beer. “I figured I’ll roll in there and there’s going to be somebody that wants to go fishing.” A few solid guides adopted Phil as a guide-in-training and razzed him into hitting his mark with the oars. “I was still a miserable rower at the time. They really schooled me up fast.”

Day by day, Phil learned his craft. The tackle shop turned out to be a good place to get information, and Phil fished hard every second he wasn’t working. “If I wasn’t working or sleeping I was fishing. That got me to where I needed to be so that I felt confident that I could start guiding the river.” The next summer he signed a two-year service contract to guide for Kenai Cache. The first year was rough and filled with disagreements but things improved the second year. “That year was better because by then I was exclusively his trout guide which is what I want to be.” In a state widely celebrated for its salmon, that’s a strange thought.

Phil’s infatuation with trout grew from fishing them as a kid. They are a resident species that feeds year-round, minus spawning season when it’s unethical to fish them. “If you’re in touch with what the trout are doing you know what’s going on with the river.” A good fly-fisherman knows what the fish are eating, which requires an understanding of the ecosystem. Then, he must replicate that ecosystem in fly choice and presentation. “It’s not like sockeye where you go out and you’re basically trying to snag them in the face.” Salmon are on an upriver trip to their breeding grounds “basically on a mission to spawn and die,” and therefore rarely eat in fresh water. “You gotta have mind tricks. Like, how do I fool this trout?” And if you do, you’re in for a good fight reeling him in. In the end, Phil may prefer trout but he doesn’t dislike salmon. He laughs, “It’s not their fault they’re not trout.”

Phil planned to spend several more years learning from other guiding outfits in preparation for starting his own. However, an exciting job prospect at a new lodge guiding under the wing of perhaps the most veteran Kenai guide fell through last minute. Suddenly adrift, without a backup plan, and past the prime hiring season, Phil couldn’t face losing a season’s experience. It was time to either hit the streets begging for a job or go all in and start his own drift-boat guiding business, ready or not. Phil anted up.

Catch a Drift

Everyone who knew Phil at that point understood his passion for fishing. People saw him working hard on the river so they supported him. “I had a decent amount of capital to get started but not enough. I could probably write a movie list of credits of people who helped me in some way.” Permits, gear, and tackle added up. Unable to find a used boat he had to purchase a new one. “Starting up was steep.” And terrifying. “The biggest feeling preseason that I had was fear. I’m investing all my money into this, I’ve taken money from other people that believe in me, I’m going out, I’m putting myself out there; I have nobody I can rely on for a paycheck other than myself.” A good friend and successful businessman bought Catch a Drift’s first fishing trip to support his young friend and kick off the season.

Bookings were slow but other guides assured him business was coming. Phil scraped by. After all, he didn’t really have any overhead other than the initial money for the boat and gear. “It’s not like I had huge payments to make other than the same cost of living I’d always had, just rent and phone.” Then, ironically, Kenai Cache called. A guide had quit so to fulfill bookings they lobbed a string of trips to Catch A Drift. Overflow business trickled in from other outfitters and Phil slowly built a customer base from independent bookings, as well. Though he didn’t have a lavish past for comparison, that first season he made more money than ever before. In one day, he could now make what used to take five days working for someone else.

Fear diminished and pure enjoyment bubbled in its wake. “It’s a dream come true. I get paid, and get paid well in-season—which, it’s a short season—go to the river and do what I love to do, and get people excited about it.” From first-timer to trophy fisherman Phil invests himself in every river trip. “I try to give everybody at least a small taste of what it is that that river means to me.” Simply put, it’s nostalgia blended with an opportunity to participate in an ecosystem. “Very few days have ever felt like work since I started guiding.” The fact is, more often than not, after dropping off clients he’s quick to grab a couple friends and go right back out fun-fishing.

Phil-osophies on Fishing

Catch a Drift guides drift boat fishing for rainbow trout, dolly varden sockeye salmon, silver salmon and steelhead on the Kenai River. Phil believes drift boats offer the best experience, allows clients to get closer to the fish without spooking them, and also cut down on pollution. Phil waxes fishing philosophic with the bewilderment of a child, the audacity of a young adult, and the ease of a professor. That is to say he’s cozy with the subject matter and his opinions fringe on controversial.

“There are some demons with it. Being a catch-and-release fisherman there is a certain mortality rate that goes along with it. Being an ethical fisherman you do everything you can to reduce mortality.” For instance, Phil encourages fishermen to pinch their barbs, something a lot people don’t want to hear. Lately, Phil’s leading by example. For the last two weeks he’s frequented a section of the river that is known for trash. After a couple hours he puts down the rod and picks up litter. In the last two weeks he’s pulled 80-90 pounds of lead out of the river, including a 50-pound anchor. He’s presently organizing manpower to join in the efforts.

“This may be smelly, but it’s a beautiful thing. Roughly a 60lb king has completed his life cycle against all odds, one of two or three of his thousands of brothers that got to perpetuate the species” -Phil Hilbruner

On a local level, Phil feels it is unethical to fish king salmon, harbingers of the impact of current unsustainable fishing practices. Low runs and smaller average fish sizes suggest kings need time to heal their population. Motorized traffic, though not prohibited in all sections of the Kenai, is further compromising the health of the fishery by, among other things, disturbing the specie’s spawning practices. “A lot of these kings are spawning in pretty shallow water. When kings spawn you get trout right behind them trying to eat up the eggs.” People fish those spawn beds to target the trout, which doesn’t affect the kings. However, after fishing a hole in their powerboat relatively quietly, they’ll “fire up the motor and run straight back up over it, right over all those spawning kings.” There are many reasons Phil doesn’t like motors, “But the biggest one is they’re unnecessary.” Perhaps for that reason every other drawback carries a little more weight.

But the fight for the fishery’s health has escalated. The Ninilchik Tribal Council recently gained permission to put a gillnet just below Skilak Lake on the Kenai River—a decision that could decimate the ecosystem. “It’s a super nonselective and lethal way to fish.” A gill net, of course, catches indiscriminately. “It’s not a tribal rights issue; it’s a subsistence community issue. They’ve come out and said they don’t have a meaningful method of harvesting their subsistence fish.” A claim that is simply not true. Subsistence communities must be a certain distance from a grocery store to be classified as such, and because of that distance they’re extended privileges for hunting and fishing. The thing is, Cooper Landing, out of which Catch a Drift operates, is also considered a subsistence community. Because they’re all fishing the same river, locals know the claim doesn’t hold water and they’re fighting the decision. “Subsistence does not trump conservation.”

It all comes back to connection with the ecosystem. “What you get from fishing is an opportunity to be an advocate for those fish. Sport fisherman are the biggest voice or the only voice to protect the fish. The more you know about them or understand them the better you can do that.”

The Future

Winters are still a work in progress for Phil. He’s considering options in other states and scheming ways to extend his season. “Winters need a change. I need more fishing and possibly better work until I get to a point I don’t have to work in the winters. That would be nice.”

Last winter Phil tied over a thousand flies. He tied for many purposes but one was his latest obsession: to hook a steelhead at the surface. “I’m on a mission for next year to try to get one from the top of the water so I’m gonna tie some top water patterns that will skate across the surface and try to entice a steelhead to bite.” Steelhead are a variation of rainbow trout that go out to saltwater for several years at a time. Phil marvels at the fish’s adaptability and the risk of swimming into a foreign expanse teeming with large predators. “They go out in this big black hole, this big void, this big tough ocean and come back as huge rainbow trout that fight hard. […] This fresh-saltwater, rainbow, ocean beast.” Unlike salmon, steelhead also have the potential to spawn multiple times, and to Phil that’s always painted them as the stronger species. “They’re my holy grail.”

Phil eats, sleeps, and breathes what he loves. During a low point in life he trustingly redirected his life toward the thing that impassioned him. A few years later, facing another low, he risked everything and did it again. In a relatively short period of time, he became owner/operator of a guiding service on a desirable river—and he’s succeeding. Regardless of whether he’s fishing with clients or friends, Phil’s engaging in what he loves. When people feel that their job is not actually work the world should pay attention. More people should be so lucky—but of course, luck has little to do with it. The forces that be may have shaped his love of fishing, but his success is the result of deliberate lifestyle choices and hard work mixed with passion. More people should live so deliberately.

On a somewhat recent trip to Hood River, Phil was stoked to see The Gorge Fly Shop still supporting it’s local fisherman. “I was back in there a couple years ago bullshitting with the guy and three kids probably ages 8-12 come in the store.” The owner welcomed the kids by name who, of course, had run out of whatever fly they were fishing with. “Okay, well, you know where it’s at—get it and get out of here,” the owner barked. Perhaps those flies, if presented right, could catch more than just fish—they certainly did with Phil.

- Book a trip with Catch a Drift

-

Hooked on fishing? Whether you’re looking to become a guide or simply improve your skills click here!