Graduation. Everyone’s asking you what’s next and their expectations are palatable. Supposedly, this is the best time of your life but you can’t wait to leave. You’re ready to sink your teeth into life’s next phase, but whether that means college or an office job, you remain unconvinced the traditional path will satiate your desires. Society beckons you with its easily-accessed roads toward average success and creature comforts, but that’s not really what you’re seeking. You need adventure, exploration, and to figure things out on your terms—creature comforts be damned. Although college is a valuable option for most careers, many people pursue their dreams without formal education. This is not an escape from education; learning simply happens in a different way. Graduation speeches propagate an idea of success that not everyone buys into. Similarly, a recently earned degree can tether you to a ladder you didn’t mean to climb. But regardless of where you are on that ladder today, you can still choose differently.

Dirk Collins, who founded two successful film production companies, is one such person. As founder of OneEyedBird Marketing & Entertainment and co-founder of Teton Gravity Research, he’s traveled to some of the most remote places in the world, worked with some of the top adventure athletes, and continues to learn knew things every day. Breaking into the film industry is difficult, and starting a production company is downright foreboding, yet Dirk never attended college. Tackling any career away from the insulated guidance of college is a vulnerable place to experience trial and error, thus four values have become pillars in Dirk’s ability to navigate the system and manifest success: progress convention, build upon past success, commitment to passion, and hard work. Of course, Dirk didn’t begin adulthood with those pillars, he learned them along the way, and with every challenge he’s learned to embrace those pillars further.

But at one time, he felt exactly like you.

Dirk recalls his high school commencement speech: “The ex-mayor of Anchorage was up there telling us how this was the most amazing time of our life and we needed to really enjoy it and the next couple of years were gonna be phenomenal and all I can remember is this is the dumbest time of my life and I can’t wait to get the hell out of here and be out of everybody’s control so I can go do what I really want to do.”

So what did he do?

#1 Progress convention

Every day, workers proffer their mental energy and stress to soulless businesses that don’t care for them in return. Many companies don’t deserve such power over their employees, yet they succeed in taking it. “I struggle with society constantly because I don’t buy into most of it and the older I get the less I believe in any of it.” Simply rejecting convention, however, is embittering. One must put that energy into something positive. Dirk invested it in skiing.

As heli-ski guides in the early nineties, Dirk and his friends, Todd and Steve Jones, pushed the big mountain skiing scene around Valdez, Alaska and Jackson, Wyoming. In the wake of Greg Stump’s instantly classic ski film, The Blizzard of AAHHH’s, they felt the then-current ski movie formula—cutaways from one powder turn to the next—lacked big mountain soul. “We’ve got our own philosophy of what ski movies should look like and we wanted to see the full line.”

All three friends were making good money fishing in Alaska in the summers. One day Dirk and Todd were hiking a couloir and they realized they had the ability to make the ski movie they wanted to see. “We know all the talent and none of these film guys can go anywhere; they want to shoot from the groomer. We need to get in there and do it. We can ski anything and climb anything.” It was a risk, but Dirk says, “it’s never safe to live your dreams.”

That conversation was the impetus of Teton Gravity Research (TGR). Among the talent was Jeremy Jones, Todd and Steve’s younger brother, who would go on to become Snowboard Magazine’s ten-time Big Mountain Rider of the Year. They used some of their fishing money to buy cameras, learned how to operate them, and over the next few years filmed Continuum and began building an adventure film brand.

These guys didn’t just reject the convention, they progressed it.

Thirteen years, 23 films, and over 70 television episodes later, Dirk itched to diversify. It would have been easy to stay with TGR, which continued to grow as a leading adventure sports platform, but the easy route has never been Dirk’s way. It was time to build something new once again. He parted TGR on good terms and started OneEyedBird, a production vehicle for building brands and messages through multimedia platforms. Once again, Dirk set out to progress conventions.

Listen to Dirk recall his nervousness at the premier of TGR’s first film, Continuum

#2 Build upon past successes

Strength coalesces from many areas in one’s life. Of all the activities Dirk was exposed to in his outdoorsy childhood, skiing fulfilled him from a young age. His story begins in Salmon, Idaho, a then-unincorporated nook of the United States that in the 1970 census boasted a population of 186. At 2, Dirk started skiing at a nearby resort. Before long, a group of local, pro mogul skiers took him under their wing and skied with him on weekends. At seven, however, Dirk traded downhill skiing for nordic skiing when his dad accepted a job in Alegnagik, a remote village in Western Alaska. He was bummed to lose skiing but adapted to his new environment.

He and his brother became the only year-round white kids in the village, something he remembers fondly. “Talk about a sick place for a ten year old to grow up, right? Boats and snowmobiles, fishing and hunting, and exploring and wandering around and playing with Eskimos and yeah, it was rad.” In fifth grade he moved to Dillingham, a larger village that these days is connected to Alegnagik by a well-maintained 25-mile road, but back then the road was always washed out, iced over, or snowed in. He transplanted from a class of a handful of kids in Alegnagik, to one of perhaps a hundred in Dillingham, to a school of around 2,000 in Anchorage.

The transition could be overwhelming for any displaced small-pond fish, but Dirk’s mom channeled her son’s troublemaking energy into something productive. Dirk began helping a commercial fisherman at Point Possession, Alaska that summer—a more intense situation than he suspects his mom was aware. “I don’t think she had any clue how dangerous that was, because it was pretty gnarly.” Dirk soon graduated into real commercial fishing and by high school was making twenty grand a summer, and essentially living without parents. “I was a total loose canon.”

But another thing Dirk’s mom did was involve her young son in junior ski patrol at Alyeska Resort, 30 miles down the road. In Anchorage, downhill skiing quickly obsessed Dirk once again and the opportunity with ski patrol got him on the hill more than they could otherwise afford at that time. There, Dirk met many of his mentors, gained professional skills, and began steering his path toward guiding. After high school, and “free of everyone’s control,” he delved deeper into the thing that made him happiest: big mountain skiing.

Dirk’s life tells of challenge and success. A kid from remote Alaska is an unlikely profile for the film industry. To manifest success, each of us must draw from our personal well of experience. How we approach obstacles defines us not only in the moment, but in future challenges, as well. Through uproot, divorce, and physical challenges Dirk learned perseverance. Although he now has many career successes to draw from, at the ground level he only had that which he held in his heart—confidence born from past challenges. By absorbing such lessons, we empower our future selves.

#3 Commitment to Passion

The word passion has been rendered meaningless through overuse, so what is it really? Passion compels you, whether you heed it or not. If ignored it will corrode and leave you hollow. It can add depth to your life and help you achieve your highest goals, but only if you make it a priority—otherwise society will calmly guide it to slaughter.

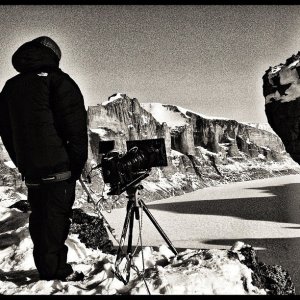

On the job: A musher and his team push on toward the Bering Sea coast en route to the finish line in Nome, Alaska during the 2015 Iditarod. Photo credit Dirk Collins

Dirk’s passion lies in storytelling through adventure. “A lot of the stuff we’ve been trying to do [at OneEyedBird] is kind of take my roots of action sports but grow them into bigger stories and feature documentaries and bigger television.” Adventure means more than just thrill-seeking. There’s an educational component implicit in travel. “Some of the most important education that a person can get or that a child can get is traveling because it creates tolerance and understanding.” It’s not enough to live somewhere special; traveling fosters something bigger by breaking down misconceptions. “You start to gain respect for other places, and other people, and other animals, and tolerance for religion and other ways of life that don’t make sense if you never leave the United States. So I think it’s critical, right? Everybody really should have to do it.”

But not everyone can so Dirk funnels the world into people’s homes and hopes to inspire social change through media. Whether he’s helping the World Wildlife Federation track snow leopards, or snowmobiling a thousand miles across Alaska filming the Iditarod Sled Dog Race, Dirk has a passion for creating content that promotes understanding. Clearly kids are plugging-in more than ever, and Dirk sees that as an opportunity. “It gives us the ability to pipe content to them so maybe we can get some good messages to them that way.” Passion is inspiration, which begets action.

“Villagers butcher a yak as children watch and learn. While on location for the WWF snow leopard project I spent quite a bit of time with the people of the village, which was amazing. No matter what part of the world they are from it is always amazing to see the skill, efficiency and lack of waste characterized by indigenous people and the food they harvest. The butchering of this yak took about an hour, start to finish. Not a drop of blood was spilled and when they were finished only a small pile of dung (from the intestine) remained. Everything else was used.” -Dirk Collins

“Every day—if it’s a bad day, or a good day, or a bad month, or a bad year—I’m still super stoked to get up and do my job. I love it. I get to work with phenomenal people and I get to go to amazing places and I learn new shit every day and, you know, a lot of it’s super dangerous and a lot of it’s hard work—actually probably all of it’s hard work—but I’m living, right? I believe in everything I do and I’ve created a vehicle right now where I have influence and can tell stories and make change.”

That is the voice of passion embraced. As Dirk states, however, passion begets hard work. If you starve passion of commitment you cheat yourself and, for that matter, the world and that is why #4 is the most important value of all.

#4 Hard work.

It doesn’t matter how much you embody the first three qualities if you don’t invest your blood, sweat, and tears into the battle. “You’ve got to fight to do what you want to do, and it’s really easy to say, ‘it’s too difficult or I’m too beat down’ or whatever and ‘I’m just going to get a normal job.’ […] I’ve just never been able to do that.” Dirk’s work ethic is revered. IMDB shares: “With experience based in adventure, Dirk is renowned for his ability to get the job done no matter the athletic challenge, remote location or harsh environment.” His passion consistently convenes with challenge, something he’s learned to embrace. “With business and life I’m always taking the most difficult path because I feel like that’s the one that’s closest to your heart.”

These days, inspirational mantras litter social media. “People love to throw around quotes from famous people or people who took risks.” But for most people, the commitment ends there. “Those things are easy to throw around but to live that is super difficult and to live that you’re going to get beat the fuck up, and so most people can’t do it. They can put it on their photo on Instagram or whatever but to actually live by that, I’ve learned, there’s not too many people that do it.” If you’re not willing to dedicate long hours and endure sleepless nights and deal with rejection, trailblazing isn’t for you.

Dirk lives amazing adventure but not without cost. Recently, two major projects ended that cost OneEyedBird a couple million dollars in lost revenue. But OneEyedBird continues to evolve and is developing several major new projects.

The first is an adaptation of Steven Kotler’s book, The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance. It studies the concept of flow, a heightened state of decision-making that enables adventure athletes to progress their sports at a never before seen evolutionary pace, which Kotler believes can be decoded and applied to advance all areas of society

The second project follows Mike Horn, perhaps the greatest living explorer today. The 48 year-old South African’s accomplishments are too extensive to list here, suffice to say, he swam the Amazon from source to sea (roughly 5,000 miles) and skied solo around the Arctic Circle and Antarctica. Now, OneEyedBird wants to develop a multimedia platform using Mike’s upcoming pole-to-pole, circumnavigational trip to create broad-scale educational content through adventure.

Both projects, however, have met resistance from the industry. “This is so phenomenal and amazing, you know? How come Nat Geo’s not jumping on this or why isn’t someone paying attention?” Even so, each barrier becomes fuel for the fire. It’s the way Dirk’s always greeted opposition his life. “Just like they’ve told us the whole time since I was a kid, they’re like, ‘you can’t do that,’ and so it’s like, ‘okay cool, then that’s exactly what I’m going to do.’” Where there’s passion and hard work, Dirk knows there’s a way.

Listen to Dirk Collins talk about determination and perseverance in his own life

Conclusion

“Not a bad commute. A herder and his yaks begin a two day walk down valley to trade potatoes and wool for firewood and millet.” Photo credit Dirk Collins

The college to corporation track, though valuable, is not suited for everyone. Graduation speeches advise you to go out and contribute to the world. Do it. But do so on your terms.

Dirk progressed the norm with TGR, which empowered him to start OneEyedBird. He’s accomplished so much, yet the future continues unfolding possibilities because he sticks by his values. “I’ve been all over the world a hundred times and met amazing people and worked for some of the best athletes in the world and got to interview crazy people and I feel like I’m just starting. That’s the cool thing, I don’t even feel like it’s really even begun.” With a healthy dose of passion and hard work, nothing is impossible.

So imagine, take risks, and create because trailblazing promises no linear path. If your passion means something to you then it will to someone else. Embrace these four pillars and never lose site of them as the world tries to crush and conform your values. Pursue your dreams to the fullest because there’s no other way. Without them, you’re not really living.

But, of course, it’s one thing to read it here. It’s another to have the courage to go out every day and live it.